11 Jan 2019

An investigation of early life infections and antibiotic use in Australian Aboriginal communities

Heavy antibiotic use can drive antimicrobial resistance, which threatens our ability to effectively treat common and serious diseases.

By Dr Trish Campbell, a Research Fellow for the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory at the Doherty Institute.

Together with researchers from the Menzies School of Health Research, we analysed the medical records of approximately 400 children under five years of age living in remote Australian Aboriginal communities in the East Arnhem region of the Northern Territory, looking at disease burden and antibiotic use [1].

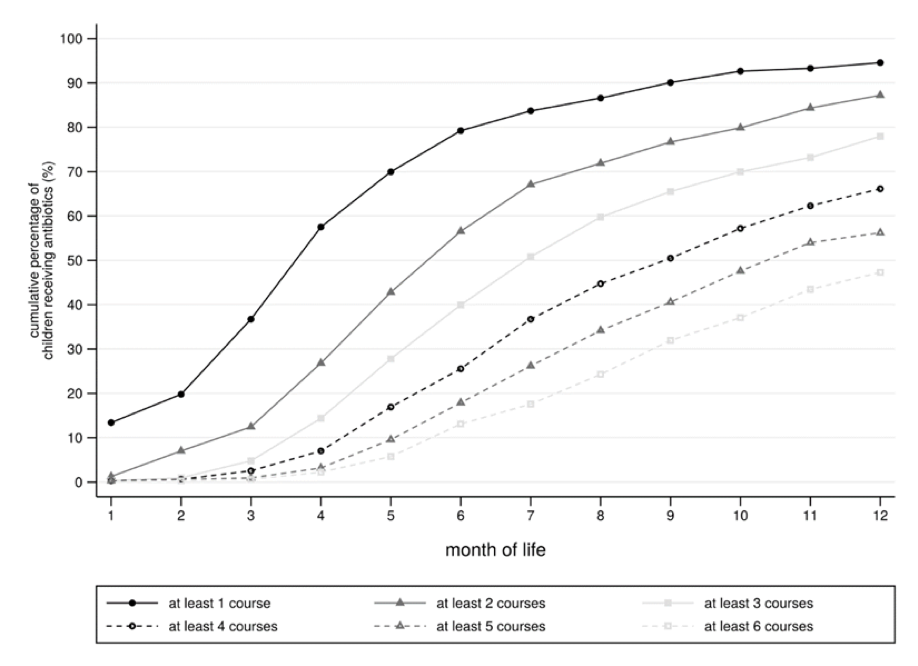

We found that these children experience a substantial burden of early life infections, such as respiratory and skin infections, with a corresponding high number of antibiotic prescriptions. Almost all children (95%) received at least one antibiotic prescription in the first year of life, and 47% of children received at least six antibiotic prescriptions before their first birthday (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Cumulative percentage of children who received up to and at least six antibiotic prescriptions over the first year of life

Few children escaped the most common infections, with 96% of the children studied presenting with upper respiratory infection and 86% presenting with skin sores over their observation period. Each month, one in every five children had a skin infection diagnosis (skin sores, scabies or fungal infection). Skin sores and scabies are regarded as ‘normal’ in these populations, and so not all of those infected will seek treatment, contributing to the difficulty in stopping the spread of these diseases.

Skin sores were a substantial driver of antibiotic prescription in these communities, with more than 50% of children receiving antibiotics for this condition. Prescriptions for skin sores remained high across the first five years of life, in contrast with those for respiratory infections, which decreased as children aged.

While we don’t have much information on how appropriate antimicrobial prescribing is in Aboriginal populations, our data show that there is a high burden of bacterial infection, which may lead to complications if not treated. We can’t simply apply antimicrobial stewardship provisions designed for urban settings to remote Aboriginal communities, due to differences in disease severity and likely causative organisms. Our work has motivated a collaborative project funded by the NHMRC HOT NORTH consortium to adapt the National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey for use in Aboriginal Medical Services, to better understand what antimicrobial stewardship should look like in Aboriginal communities.

Prevention of infection is paramount. Preventative efforts, such as appropriate housing, access to working hygiene hardware (like taps and washing machines) and health literacy are key to reducing the infectious disease burden and the antimicrobial prescribing that goes with it. We will continue to work with Aboriginal communities so that together we can tailor interventions that will work for them and meet their needs and priorities.