08 Oct 2018

Back to the future: Lessons learned from the 1918 influenza pandemic

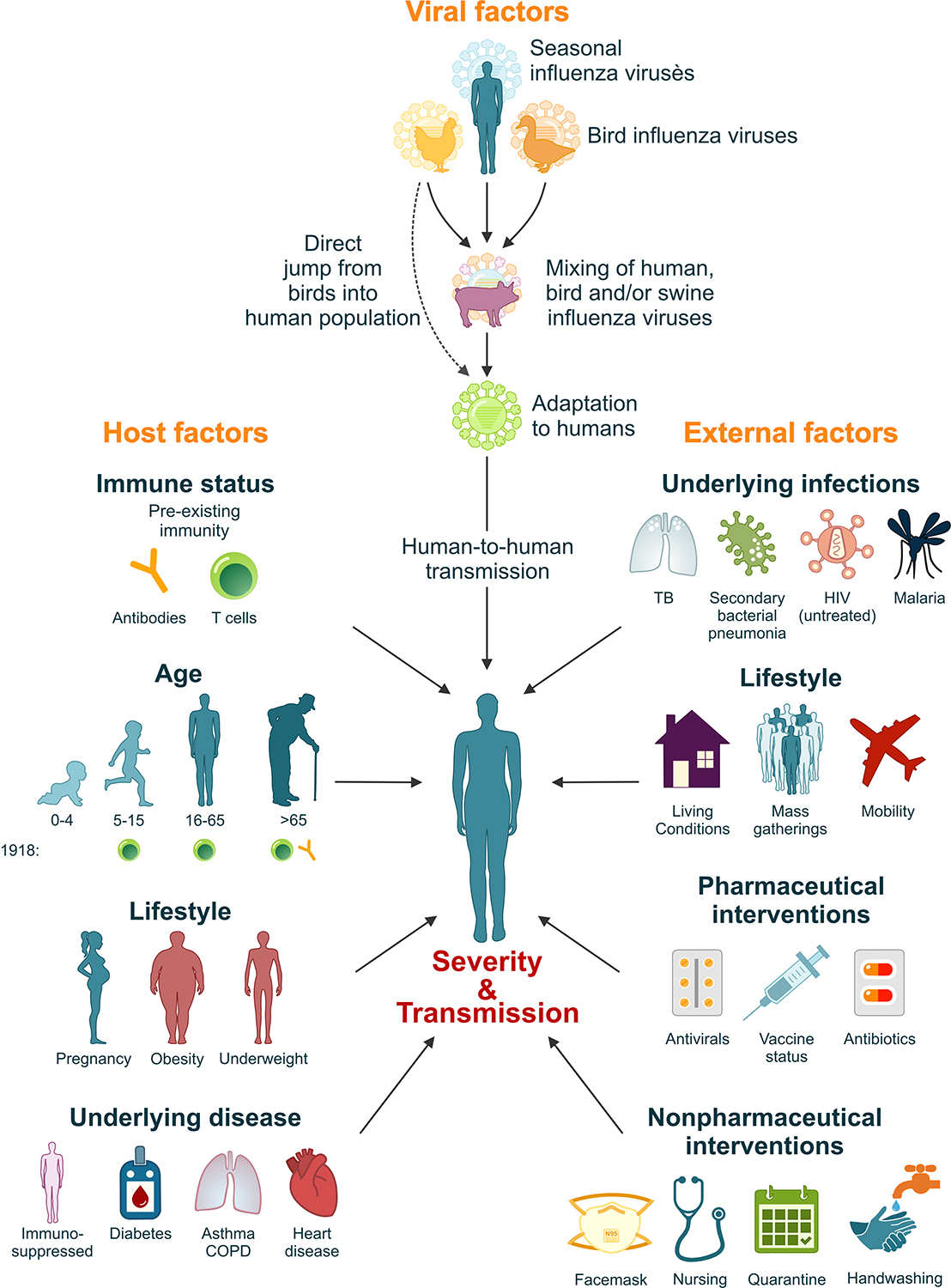

A new study has given a compelling insight into the human, viral and societal factors of the 1918 flu pandemic providing lessons on how to prepare for future flu pandemics.

Published in Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, researchers from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) and the University of Queensland took a deep dive into the lessons learned from the pandemic, 100 years on.

The 1918 influenza pandemic killed approximately 50 million people – this study explores factors that contributed to the severity of the pandemic, why it was more virulent than previous influenza pandemics and why some people survived and others didn’t.

Authors, University of Melbourne Professor Katherine Kedzierska and Dr Carolien van de Sandt of the Doherty Institute and Dr Kirsty Short of the University of Queensland did a comprehensive review of a large number of studies of the 1918 pandemic.

“We always wondered why some people can effectively control viral infections while others succumb to the disease,” Professor Kedzierska said.

Some studies showed the virus strain could spread to other tissues beyond the respiratory tract, in addition the virus had mutations that allowed it to be more easily transmitted to humans.

The study identifies public health as playing an important role in the 1918 pandemic, which could apply to a future pandemic.

“100 years ago, people who suffered from malnutrition and other diseases, such as tuberculosis were more likely to die. Malnutrition could be a factor now, again with climate change leading to crop losses. Bacterial infections may increase with antibiotic resistance,” Dr van de Sandt.

“Today, society faces the issue of obesity, which increases the risk of dying from influenza.”

Young adults were one of the most severely affected in the 1918 flu pandemic, with researchers thinking older people may have immunity after being exposed to other viruses.

Dr van de Sandt said it was also strange that mortality in school-aged children was relatively low, and the reasons are not understood.

“Researching this phenomenon could reveal new ways to fight influenza,” she said.

“Birds are a major reservoir for new variants of the influenza virus. Climate changes may affect bird migration patterns, which means that potentially pandemic viruses could spread to new locations and across a wider range of bird species,” Dr van de Sandt said.

The study showed that cities that introduced hand washing and banned public gathering helped to reduce infection and death during 1918, but only when applied early and for the duration of the pandemic.

“Until a broadly-protective vaccine is available, governments must inform the public on what to expect and how to act during a pandemic,” Dr van de Sandt said.

“An important lesson from the 1918 influenza pandemic is that a well-prepared public response can save many lives.”