18 Jul 2017

Fascination with microbes was Q to study cattle industry scourge

Hayley Newton and Catherine Satzke accepting their Frank Fenner award

Dr Hayley Newton is leading research at the Doherty institute into an organism first traced to Queensland, that became a centrepiece of US biological warfare experiments in the 1950s, and remains a threat to livestock and humans today. Earlier this month, she was awarded the Australian Society for Microbiology Frank Fenner Award, in recognition of her distinguished contribution to microbiology research.

In 1935, abattoir workers in Queensland came down with sudden and severe symptoms of fever, chills, muscle aches, loss of appetite, disorientation, and profuse sweating.

Fearing the outbreak would be bad business for the cattle trade, authorities quickly dubbed the flu-like disease “Q fever” (“q” for “query”).

Samples were sent to Melbourne for analysis, and two years later, the organism responsible was identified as Coxiella burnetii, after its co-discoverer, Nobel Laureate Frank MacFarlane Burnet – who caught the disease in the lab.

It didn’t take long for this bacterium to attract the attention of researchers in the USA and Russia for its potential as a biological weapon. Easily spread via dust or droplets, it can hide out in soil, bedding straw or wool, withstanding heat and cold. It can also be spread via unpasteurised milk. Often, it only comes to the attention of farmers when livestock suffer spontaneous abortions or slaughterers come down with a flu-like illness. In rare cases it is fatal but can have a severe impact on people with pre-existing heart conditions and pregnant women.

The infamous Operation Whitecoat human experiments demonstrated that inhaling very few Coxiella could cause infection. They were performed at Fort Detrick Maryland on conscientious objectors who opted to “take a germ bullet” rather than go to war in Vietnam.

Hayley Newton started her research on Coxiella during postdoctoral studies at Yale, just as scientists were working out ways to cultivate it in the lab. Her undergraduate degree had opened her eyes to the huge impact tiny microbes could have on people’s lives.

“I’m really fascinated by bacteria that are able to invade human cells and take them over from the inside,” Dr Newton says.

She had worked previously on legionella. “They’re closely related, so we still occasionally do some Legionella work,” she says. “It’s great to compare and contrast these two intracellular bacterial pathogens.”

Coxiella is an obligate intracellular pathogen, meaning it normally only grows inside human and animal cells. In 2009, scientists at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIH, finally managed to grow it in the lab, after working tirelessly to provide the right environment and nutrients.

Dr Newton was one of the first scientists to succeed in genetically manipulating Coxiella and identifying bacterial factors that are important for disease. Her pioneering techniques have demonstrated that the secretion system set in motion when the pathogen takes over cells is an important determinant of virulence.

She says the cell biology of Coxiella infection is fascinating, as the pathogen replicates to extremely high numbers within the host cell lysosome. A lysosome is the cellular equivalent to Mars – a hostile place with a very low pH where all other bacteria succumb to an assault from enzymes designed to degrade microbes and nutrients. Coxiella is the only known bacterium that not only survives this environment but actually requires it to thrive.

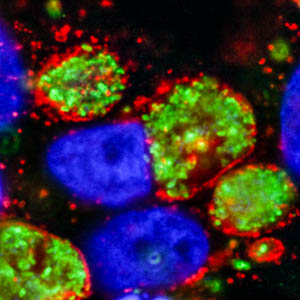

Coxiella bacteria

The immunofluorescence image above shows human HeLa cells infected with Coxiella, showing host nuclei (blue), Coxiella (green), LAMP-1 (red – a lysosome membrane protein), showing how the bacteria take over the host cell to replicate to very high numbers.

Understanding how Coxiella manipulates the human host cell to set up this unique replication factory is a key goal of research in the Newton laboratory. They use a range of approaches to identify and characterise the Coxiella virulence factors.

“Many of these Coxiella proteins that are required for disease manipulate important human processes,” Dr Newton says. “Our research is shedding light both on how Coxiella causes disease and different ways in which human cell biology can be manipulated by pathogens.”

In 1994, Australia developed a vaccine for humans and animals, but coverage has been low. The disease can be treated with antibiotics, raising the spectre of drug resistant strains.

In the 2000s, the largest ever outbreak occurred in the Netherlands, where more than 4000 individuals contracted the disease as a result of widespread goat infections in farms. Tens of thousands of goats were culled, the industry collapsed and more than 300 million euros were spent to control this outbreak.

In Australia, the biggest farm-based outbreak happened two years ago in Victoria, prompting the Farmers Federation to launch a campaign to encourage everyone in the meat industry supply chain to get vaccinated.

To this day, the original source of that 1937 outbreak is still unknown, but bandicoots are a prime suspect in a wildlife line-up that includes kangaroos and feral goats, with ticks as the middleman (even snakes get it).

This award is acknowledgement of Dr Newton’s outstanding research contributions to date and she is excited that it will also open new doors for collaborations in the future.

Previous Doherty Institue recipients include Ben Howden and Elizabeth Hartland. Dr Newton's work has appeared in journals such as PLoS Pathogens, Nature Communications and the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Q fever outbreaks in unexpected or improbable settings:

- Infection of a poker-playing group exposed to an infected cat giving birth to kittens in the same room.

- Infection of actors in a Nativity play involving a shepherd and his dog.

- Outbreak in a school of arts – possibly associated with unpacking a statue wrapped in straw.

- Q fever outbreak in a cosmetics factory at which manufacture included powdered sheep placenta and foetal tissue.

(Source: Professor Barry Marmion / CSL Biotherapies, A Guide to Q Fever and Q Fever Vaccination, 2009)