06 Jun 2022

Issue #108: Vaccine protection against Long COVID: findings for a large pre-Omicron data set

Written by Nobel Laureate Professor Peter Doherty

In trying to understand whether vaccination protects us against the development of Long COVID (LC), we considered (#105 #106) recent data from the UK National Health Service (NHS) and the Office of National Statistics (ONS) cumulated during the timeframe where variants of the Omicron SARS-CoV-2 strains were causing the majority of infections. The conclusion from this analysis was that, yes, vaccination does help by, at least for a time, lessening the likelihood that we will be infected in the first place. Beyond that, though, there was evidence of at least some LC in 8-9% or so of people who suffered a breakthrough infection (BTI) after being triple vaccinated.

By the time that analysis was done (#106), there were simply too few unvaccinated people in the UK who had not been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 to come to any useful conclusion about vaccine protection against LC in an ‘immunologically naïve’ population. Vaccine refusal has been much more common in the USA.

In the US, where veterans have their own health care and hospital system, the Department of Veterans Affairs maintains a massive disease data base. While it reflects the ethnically diverse nature of the US military, it does have the limitation that about 90% of the subjects are male. Accessing that source for January to December 2021, investigators (‘data miners’) asked whether, following BTI, vaccination protects against the development of LC.

The criterion for inclusion in the BTI set was testing positive with a PCR test 14 days or more after a single dose of the Ad-vectored J&J vaccine (like AstraZeneca, though we had two shots), or the second dose of the Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccines. The analysis is limited to the six months after infection and excludes any subjects who died during the first month. The overall rate of BTI was 10.6 per thousand vaccinees.

The investigators compared the LC profiles for some 33,940 vaccinated BTI cases versus 113,474 subjects who were completely unvaccinated at time of infection. Additional to that, comparisons were made with a control population of five million people who did not contract COVID-19. When we look at five million people over a six-month period, some will inevitably die or become symptomatic as a consequence of other medical problems. Also, any who had a subclinical SARS-CoV-2 infection, or failed to report a case of COVID-19, would be included in the control group.

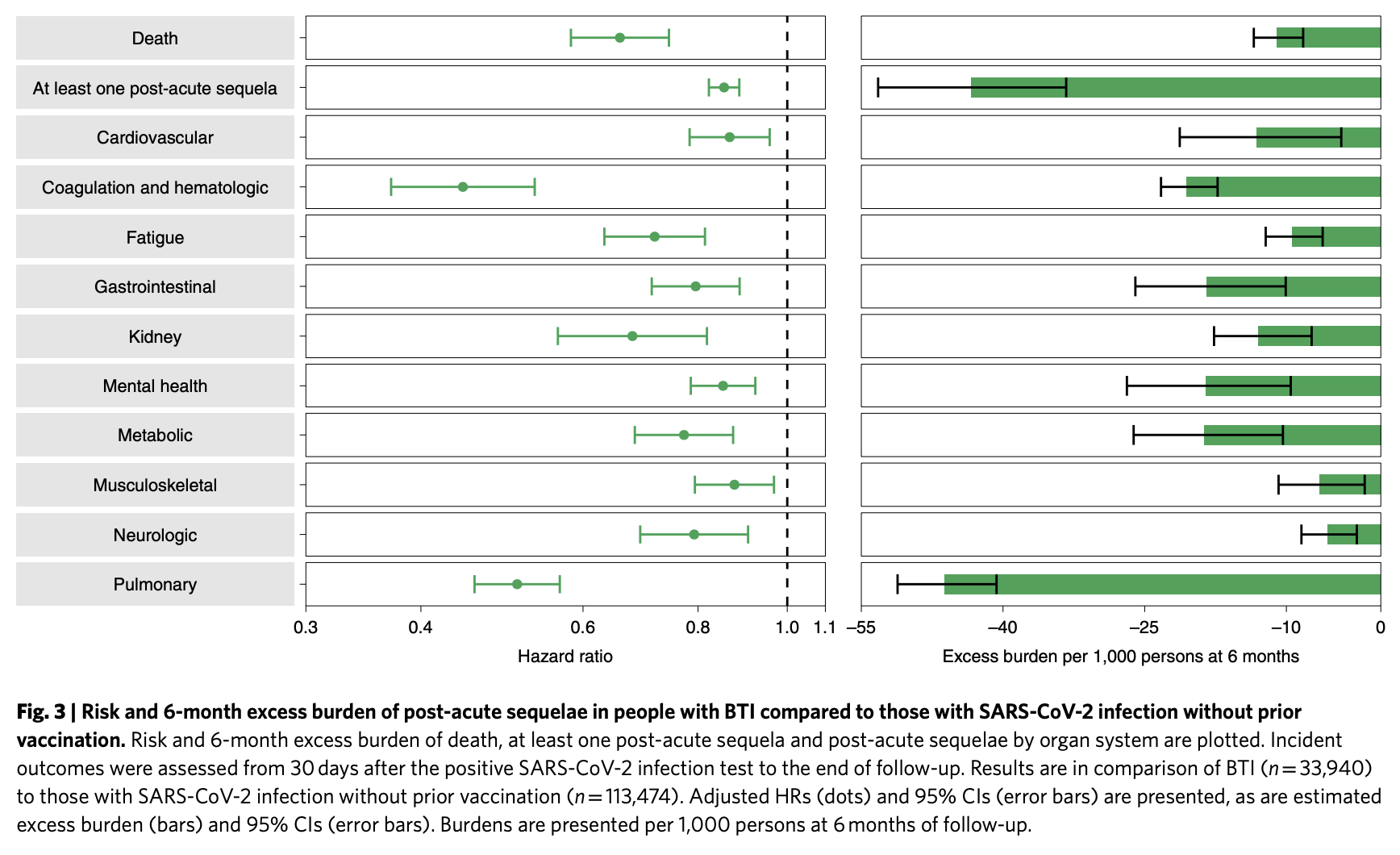

Putting numerical values on what is happening here takes most of us into unfamiliar territory. I struggled with some of this, but the following is my best understanding. A ‘-‘ in front of any number tells us that the risk is reduced. The results are expressed as Hazards Ratios (HRs) plus an estimated value for disease burden. An HR of 1.0 means that the level of risk is essentially identical for two different groups, 0.5 says that risk is halved for the ‘treatment’ group while 1.5 takes us in the opposite direction.

The disease burden is an estimate of severity of clinical compromise per 1,000 people to the six months after infection time point. This is well illustrated in several figures in the paper. If, for example, we take the separate disease burden estimates for all post-acute sequelae and pulmonary compromise for BTI versus infection in unvaccinated people, they both average out at about -45. That result is from Figure 3 in the paper: you will understand this better by looking at Figure 3 than you will from anything I write here.

Compared to the uninfected controls, cases who survived the first 30 days of BTI exhibited an increased risk of death (HR = 1.75) with an excess burden of 13.36. Those with BTI also had an increased risk of experiencing at least one symptom characteristic of LC (HR = 1.50) and a burden of 122.2.

Comparing the risk of death (from 30 days to six months after SARS-CoV-2 infection) for the vaccinated and unvaccinated populations, the HR was 0.66 with a burden of −10.99 . When it came to symptoms of LC, estimated by looking at a spectrum of organ involvement, the HR was 0.85 with a burden of −43.38 in favour of the vaccinees. Overall, the risk of post-acute sequelae in the examined organ systems was lower in the BTI group for 24 of the 47 sequelae examined.

There are, of course, many other research papers detailing the likely effects of vaccination when it comes to both preventing death and the development of LC from the SARS-CoV-2 strains circulating through 2021. Where this publication is particularly useful, though, is in the size of the data sets. Beyond that, it separates out estimates of LC clinical compromise (burden) for people who are well enough to stay at home through a six-month course of the disease versus those who could be suffering permanent organ damage reflected by the need for hospitalisation or, beyond that, an ICU stay (click on the link and look at Figures 2, 3 and 4) What may be encouraging in the context of the current Omicron surge is that this variant generally sends fewer patients to hospital. Hopefully, that will mean it is less likely that people will develop the severest aspects of LC. Time will tell.